Home » News & Events »

Press Gangs and the Kings shilling!

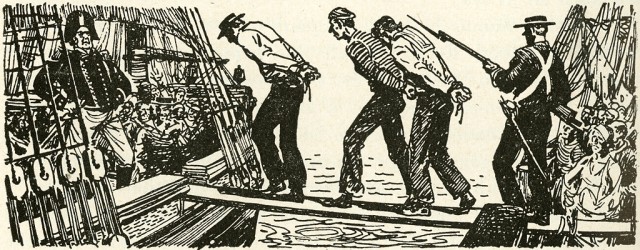

The practice of impressment (also known as shanghai-ing or crimping) was common in all the world’s ports until about 1820, and was widely used by Britain’s Royal Navy to maintain crew numbers on its warships.

Press gangs (derive from the term impressment, which can be defined as, the act of coercing someone into government service) were used by the Royal Navy as a crude and violent method of recruiting seamen into naval service, often against their will. Recruiting sailors voluntarily was difficult as the conditions on board ship were poor and serving in the navy, especially at time of war, was, well dangerous!

The practice was at various times given parliamentary authority. Impressment was vigorously enforced during the naval wars of the 18th century by Acts passed in 1703, 1705, 1740 and 1779.

The press gang, normally a group of 10 – 12 men, led by an officer, would roam the streets looking for likely ‘volunteers’, merchant seamen were particularly prized as they already had seagoing experience and needed less training.

Certain groups were theoretically exempt from the impressment process, i.e apprentices and officially foreigners could not be impressed, although they could be persuaded to volunteer and there was an age limit 18 to 55 years. But the rules were very often ignored so that the press gang could earn their reward, as they were paid by the head.

Often men were knocked unconscious or threatened and it was common for violent fights to break out, fuelled by alcohol, as groups tried to prevent friends or work mates being impressed into service by the despised press gangs.

A recruiting sergeant of the time once wrote:

…your last recourse was to get him drunk, and then slip a shilling in his pocket, get him back to your billet, and next morning swear he enlisted, bring all your party to prove it, get him persuaded to pass the doctor. Should he pass, you must try every means in your power to get him to drink, blow him up with a fine story, get him inveigled to the magistrates, in some shape or other, and get him attested; but by no means let him out of your hands!

Not surprisingly corruption was rife, many wealthier men escaped impressment by simply bribing the press gang, other men would play the very dangerous game of taking the King’s shilling and then running away often repeating the act elsewhere if they weren’t caught and knocked unconscious first!

It wasn’t all plain sailing though! In 1747, a British Commodore began kidnapping sailors and working men in Boston, (Impressment extended to all the colonies) and the people of the city wouldn’t stand for it. Three days of violence followed, in a riot that pitted the working class of Boston against the Colonial government and Royal Navy.

It worth adding that aside from ‘official’ press gangs, it wasn’t unheard of unscrupulous merchant and even pirate captains to use a more…’streamlined’ system shallop we say, where unwitting conscripts woke up to find themselves on board a ship miles out at sea with a lump on their head and the prospect of not seeing land again for many many months!

It worth adding that aside from ‘official’ press gangs, it wasn’t unheard of unscrupulous merchant and even pirate captains to use a more…’streamlined’ system shallop we say, where unwitting conscripts woke up to find themselves on board a ship miles out at sea with a lump on their head and the prospect of not seeing land again for many many months!

After 1853, the need for press gangs diminished, at this time the navy introduced continuous service for sailors with a more structured career and a pension on retirement, this led to more men joining on a voluntary basis and reduced the need for impressment.

The Royal Navy grew from 270 ships in 1700 to about 500 in 1793 and almost 950 vessels in 1805. The larger size fleet required more seamen. In peacetime, the numbers were much less than in today’s Navy and varied from 12,000 to 20,000 men during the Eighteenth Century. In wartime, strength increased from 40,000 in the Wars of 1739-1748, to 150,000 at the peak of the Napoleonic Wars.

Shown here is c1770 in date naval midshipman’s pressgang tool. This rare item would also have been used during naval boarding attacks and keeping sailors in line. The head is lead filled and the sailor hand stitched and tarred the surface. The spiral shaped handle is made from whale Baleen (the filter-feeder system inside the mouths of whales).

back to posts